When Dreams Go to the Movies

Making a film is a lot like raising a mule. You pour in love, money, and back-breaking labor, and just when you think it’s ready to win prizes at the county fair, it kicks you square in the head in front of the neighbors.

A film is a dream, plain and simple. François Truffaut, a Frenchman with a name that sounds like a cologne, once said movies are confessions. He’s right. They’re confessions that you spent three years arguing with actors, producers, and the Almighty Weather, and still believed strangers would pay ten dollars to hear your side of it.

Orson Welles said making a movie was like raising a child. He should have added: it’s like raising a child who steals your wallet, wrecks your car, and then moves in with Netflix.

Werner Herzog, who seems to dream nightmares for a living, called films “articulated dreams.” Which is a polite way of admitting he wakes up screaming and then charges us admission to watch.

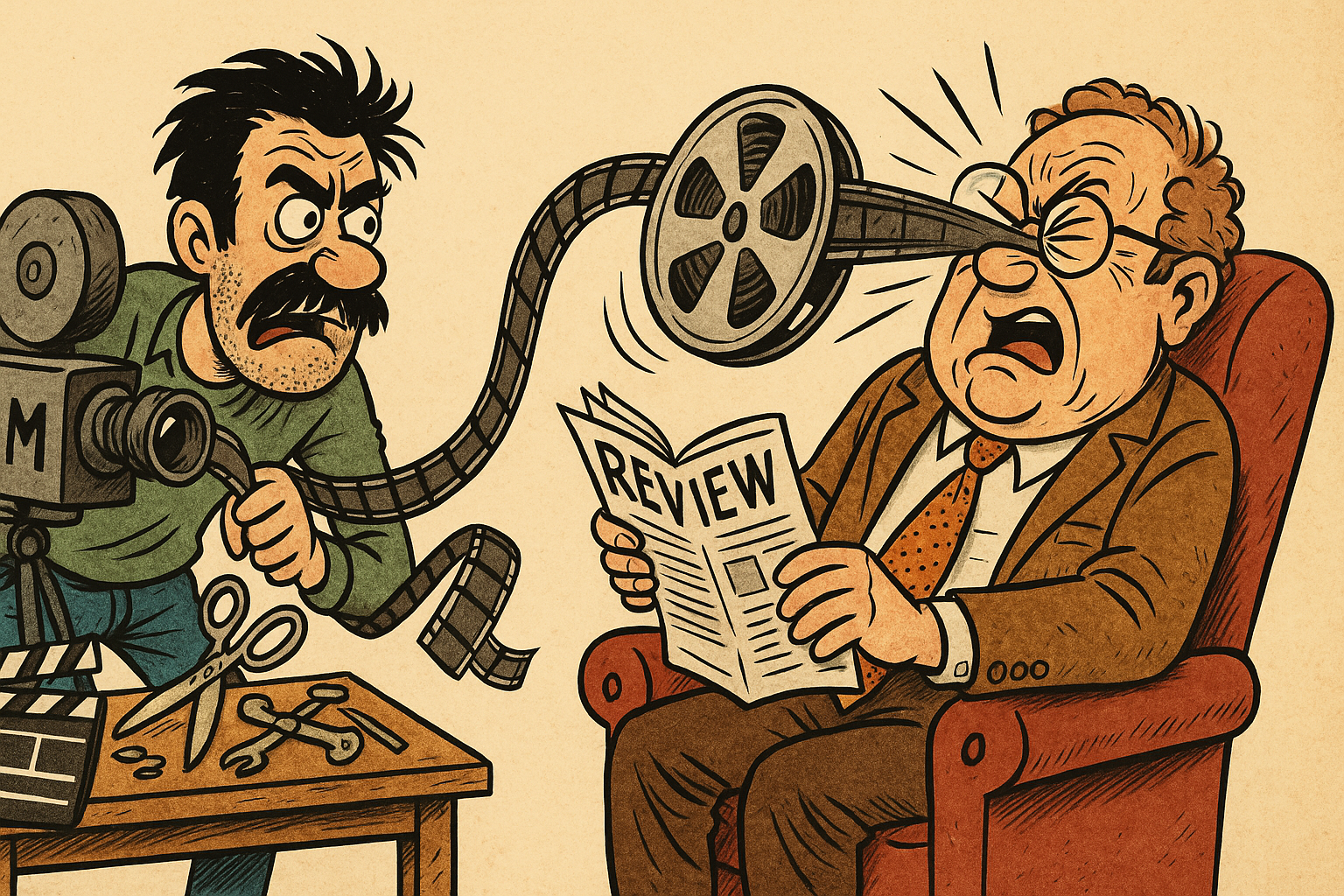

Now, if filmmaking is a dream, film criticism is the morning after. Critics live in the shadows, sharpening their quills. Pauline Kael admitted reviews are autobiography. Read her on a bad day and you can practically see what she had for lunch.

Roger Ebert confessed critics write more for readers than for filmmakers. Which explains why his prose could be kinder to a bag of popcorn than to a $200-million epic.

Susan Sontag insisted criticism was an art. Maybe so. But then so is dentistry, and both involve someone leaning over you with sharp tools and no anesthetic.

And here’s the comic twist: sometimes a critic decides to make a movie. This is like the man who mocks your dancing suddenly tripping over his own shoelaces. Kael tried her hand in Hollywood, came home looking like she’d been caught in a chicken coop during a cyclone. Truffaut swapped his critic’s chair for a director’s seat and discovered leading the charge was harder than sniping from the bushes. Rod Lurie, once a saber-rattling reviewer, made films of his own—and found out his sword turned into a butter knife.

When critics fail, filmmakers laugh loud enough to rattle the popcorn buckets. “See?” they say. “He couldn’t even direct rush-hour traffic.”

The truth is, both jobs are personal. A film is a dream made flesh. A review is a dream about that dream. They duel in public, and sparks fly. But only one side risks everything—the filmmaker. The critic only risks his dignity, which, in some cases, he lost years ago.

So next time you sit down in a darkened theater, remember: the poor fool on the screen has given you his mule. Don’t be too surprised if it kicks.