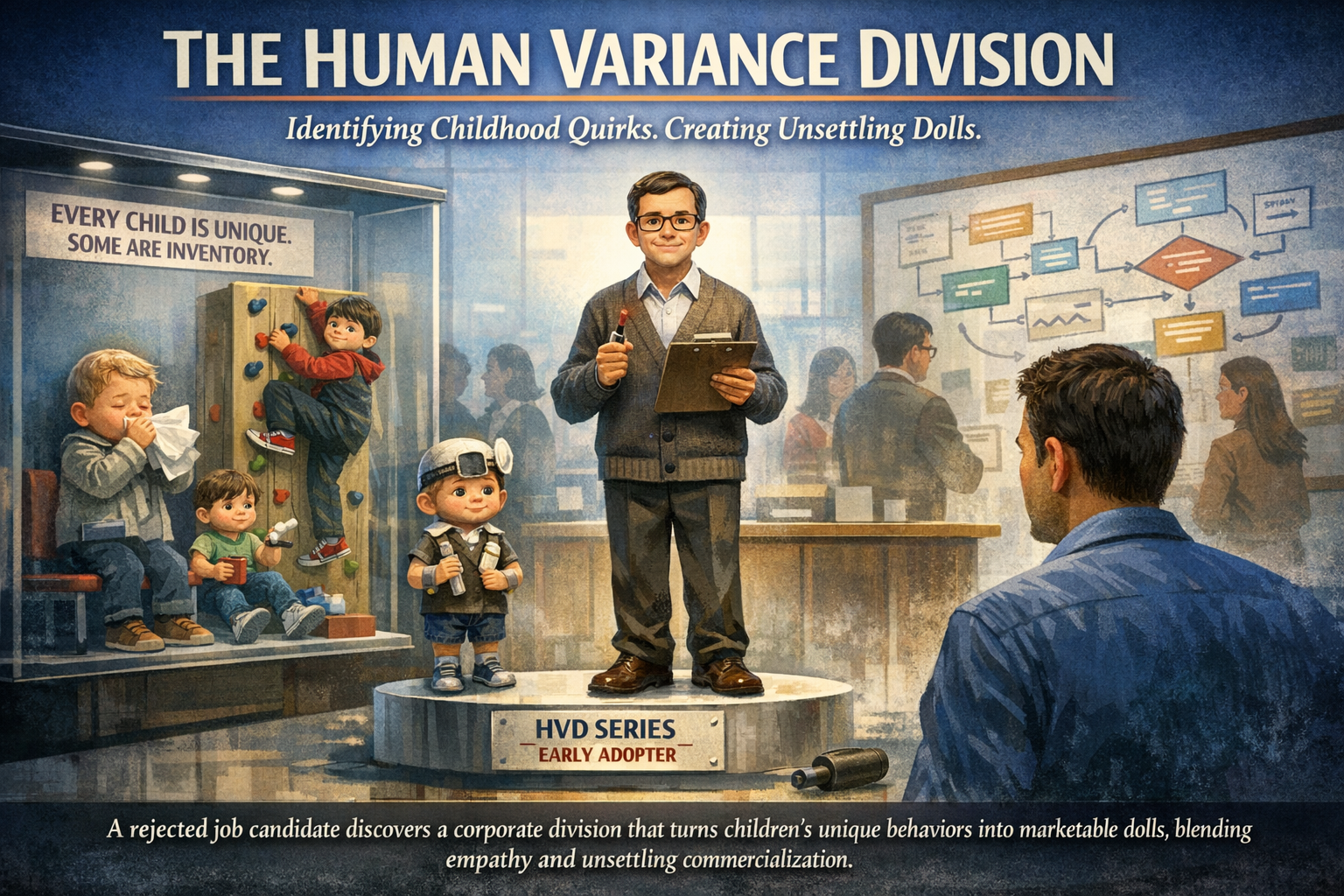

THE HUMAN VARIANCE DIVISION

W…ritten by

Jaron Summers © 2026

The job interview began with a nondisclosure agreement so thick it could have doubled as a flotation device.

That was my first indication this wasn’t a position involving glitter, tiny handbags, or anything that squeaked.

The email came from Plastikkind International, a global corporation whose reach extended into every nursery, airport gift shop, and unregulated shipping lane on Earth.

They manufactured dolls, values, and the occasional mistake—most famously the short-lived Assassin Doll, a product so disturbingly competent it was removed from circulation before anyone could determine which department had approved the silencers.

No job title. No salary range. Just a subject line that read: We’ve been watching you. Which, in hindsight, was less charming than they probably intended.

At headquarters, a receptionist handed me a badge labeled TEMPORARY CONSULTANT – HVD.

“What’s HVD?” I asked.

She leaned closer. “Human Variance Division.”

Then she smiled the way people do when they’ve already signed something irreversible.

The conference room was filled with adults who looked like they had once been fun. Charts covered the walls—flow diagrams, color wheels, something involving a funnel. One large poster read:

EVERY CHILD IS UNIQUE. SOME ARE INVENTORY.

A man in a cardigan cleared his throat.

“We used to make dolls aspirational,” he said. “Doctors. Astronauts. Presidents.”

He paused.

“That era ended when children stopped aspiring and started exhibiting.”

The mission of HVD, I learned, was to identify overlooked human conditions and convert them into marketable empathy. Or, as they preferred to say, dollize lived experience.

A woman with a laser pointer clicked to the first slide: PIPELINE OF POTENTIAL CONDITIONS. At the wide end was CHILDHOOD. At the narrow end: HVD.

“Representation is infinite,” she said. “Shelf space is not.”

They began with Chronic Sneezers.

“These children sneeze six or more times consecutively,” the cardigan man explained. “Not allergies. Something… existential.”

The doll came with a permanently raised tissue, a box of miniature antihistamines, and a warning label: May trigger empathy.

Field testing went well until the sneezing mechanism jammed. Twelve dolls began sneezing nonstop in a daycare center for three straight hours.

“Parents complained,” someone said, “that it was too accurate.”

Next came Free Solo Children—kids irresistibly drawn to vertical surfaces.

“They reject ropes,” the laser woman said. “And rules.”

The prototype doll had chalked hands, scuffed knees, and a serene smile that unsettled focus groups. During testing, one child used the doll as inspiration and climbed a grandfather clock.

“The flaw,” the cardigan man said gently, “was not the doll.”

Then there were the Percussive Timekeepers.

Some children regulate rhythm by taping a spoon to their skull.

“It’s neurological,” they explained. “And deeply irritating.”

The doll included three spoons, hypoallergenic tape, and a helmet “for quiet play.” Unfortunately, during field testing, several non-Percussive children began taping utensils to themselves in solidarity.

“We accidentally started a movement,” the laser woman admitted.

Other projects had fared worse.

A Narration Doll designed for children who announce their actions aloud was recalled after parents reported it had begun narrating their behavior.

“I am opening the fridge,” it said. “I am making poor choices.”

At lunch, I asked how HVD discovered new conditions.

“We listen to parents,” they said.

Parents, it turns out, submit symptom reports with impressive creativity: A daughter who organizes groceries by emotional temperature. A son who apologizes to furniture. A child who corrects grammar during arguments and then weeps.

“These are not flaws,” the cardigan man said. “They are opportunities.”

They showed me the CLASSIFIED WALL—behaviors not yet dollized.

Children who smell books before reading them. Children who clap when sentences end properly. Children who whisper apologies to the air.

“That’s where you come in,” they said.

The final interview question was blunt.

“Can you look at a child,” the laser woman asked, “and see a product?”

I thought of my own childhood habits. Counting steps. Assigning personalities to spoons. Believing water fountains were judging me.

“I think,” I said carefully, “that children are complicated.”

They nodded sympathetically.

“So is manufacturing.”

I didn’t get the job.

A week later, curiosity got the better of me and I returned to Plastikkind’s lobby, pretending I’d left my dignity in the parking lot.

The receptionist didn’t recognize me. Or rather, she recognized me too well.

“Your interviewer isn’t available,” she said. “But you can visit the showroom.”

Behind a glass wall stood a new display. Bright lights. Neutral carpeting. A pedestal. On it was a doll wearing a cardigan.

The resemblance was unsettling. Same mild smile. Same posture of patient disappointment. Same expression of a man who had once explained something slowly and meant it.

The placard read:

HVD SERIES – EARLY ADOPTER

This doll listens carefully. This doll nods. This doll explains why your feelings are valid but not actionable.

Accessories included a clipboard, a laser pointer, and a removable conscience.

I pressed the button on his back.

“It’s complicated,” the doll said. “So is manufacturing.”

The receptionist leaned in. “Field testing,” she whispered. “Turns out prolonged exposure to human variance eventually qualifies anyone.”

I backed away slowly.

On my way out, I sneezed seven times in a row.

No one wrote anything down.

Somewhere, a tiny silencer rolled across the showroom floor.