W…ritten by

Jaron Summers © 2026

My father often told me how rough things were when he was five years old.

He told me these stories when I was five.

Which now strikes me as either bold parenting or a man talking to himself through a smaller, more cooperative version of himself. Fathers were doing generational therapy long before it was billable.

Oddly enough, life was terrific for my dad when he was five. His mother adored him. His older brother and sister thought he was cute—though even then, a bit goofy. A promising start.

His sister Ivie wore a uniform. World War One was raging. His brother Claude, ten years older, was already thinking about joining the Canadian Army. History was happening loudly, but my father was still young enough to believe adults knew what they were doing.

Then one October afternoon, he came home from school and found a large, unpleasant adult sitting in the living room.

The man reeked of tobacco, sweat, and peppermints. He scowled with professional commitment.

That was the first time my father met his father.

Poor Grandpa Summers had been wounded in the war and couldn’t do much. A chunk of shrapnel was still lodged inside him. The army surgeons, with deep regret and impressive vagueness, said it would kill him eventually.

They just couldn’t say when.

Or if they could, they chose not to.

This uncertainty made Grandpa edgy. And when Grandpa Summers got edgy, his preferred coping strategy was to smack the nearest small male child who wandered into range.

Which may explain why my father, years later, when he felt edgy, was occasionally driven to cuff me whenever I drifted into what appeared to be a hereditary striking zone.

Money was scarce. Food was scarcer. There often wasn’t enough for Grandma and the three kids.

But because of his war wound, the doctors instructed Grandpa to eat one hard-boiled egg every day.

They raised chickens.

So the eggs went to Grandpa.

The children watched.

Grandpa also announced that he needed to eat chicken twice a week. The doctors hadn’t said that, but Grandpa felt they would have if they’d thought it through. The chickens lived brief, anxious lives.

Once a year, on my father’s birthday, Grandpa would perform a small ceremony.

He would crack the top off his boiled egg and hand it to my father.

That was Dad’s birthday present.

No wrapping paper. No candle. Just the warm, sulfurous crown of an egg—bestowed like a sacrament. A reminder that generosity, in that house, came measured in shell fragments.

Years later, my father told this story to his best friend Doug, an MD. They met in a small town near Calgary, after work, and drank a bit too much—as men who had seen wars were entitled to do.

Doug, himself a World War Two army surgeon, thought the egg story was hilarious.

He said his own childhood in Saskatchewan had been grim. The family was often short of cash. When times were especially hard, they had Point for dinner.

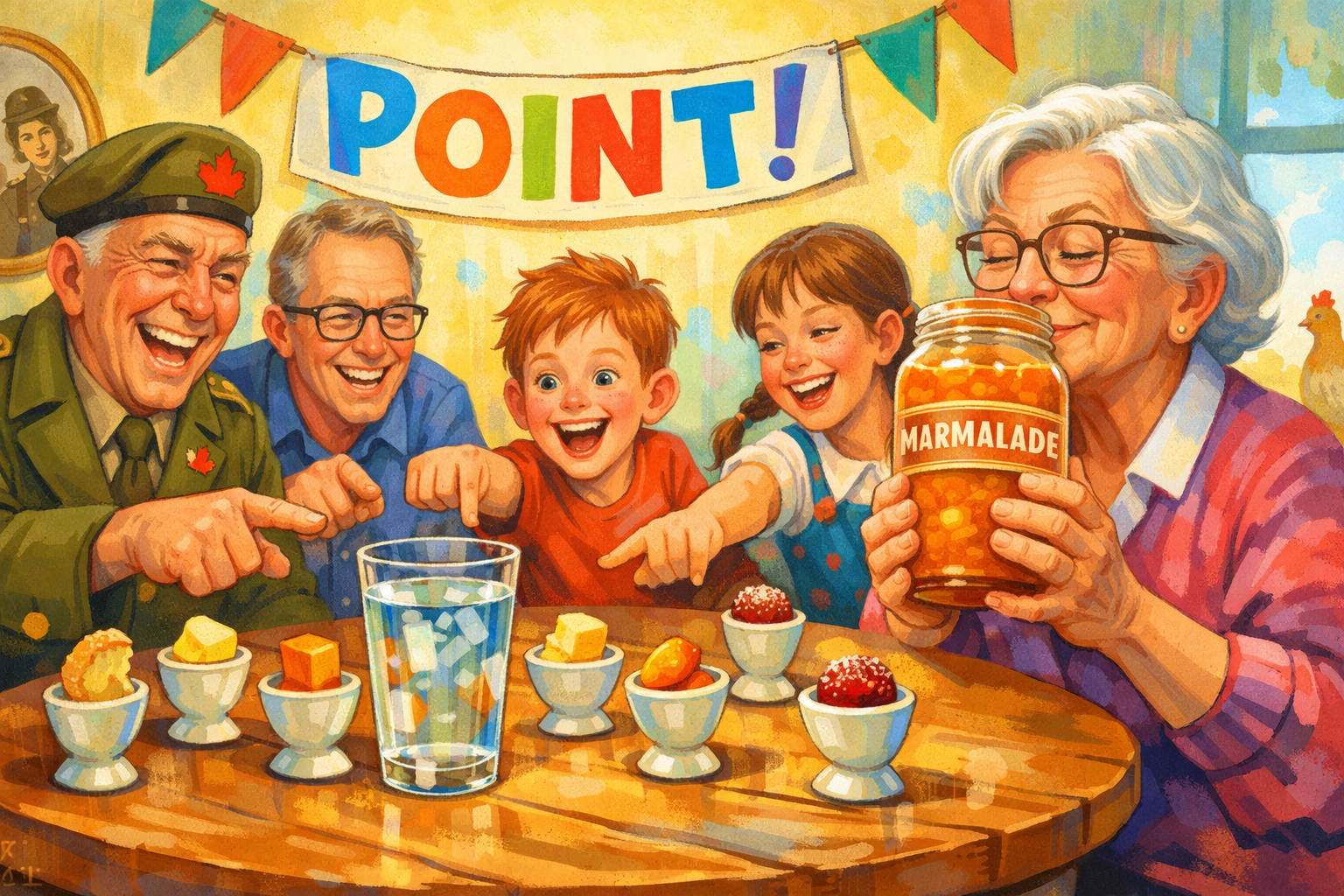

Point, Doug explained, came from Scotland, where his family was from. The family would sit around the table. In small egg cups there would be a bit of bread, a hunk of cheese, part of a fried potato, some marmalade, and a bit of fruit smothered in sugar. Each child also had a tall tumbler of water.

They would take a sip of water and point to one of the egg cups.

That was what they ate.

Then another sip. Another point.

That’s how they got through the hard times.

Doug told this without bitterness, as if describing an old medical technique that no longer required explanation. My father laughed—maybe a little too loudly—and poured another drink.

Between the cracked egg and Point, they seemed to agree on something important: if you ritualize scarcity, it hurts less. Sometimes it even becomes funny.

Thanks to good luck, a strict and loving father, and a supportive Uncle Doug, things went well for me.

Now I’m in my eighties.

My wife Kate and I have had a wonderful life. We’re healthy. Still amused by each other. But a bit light on funds. Kate loves marmalade. We are both, frankly, a little heavy.

So I’ve invented my own version of Point.

We make Jell-O.

We then open a jar of real marmalade and sniff it deeply, reverently—like sommeliers of citrus. We eat the Jell-O while inhaling the aroma, which somehow convinces our bodies that we are consuming vast quantities of delicious marmalade.

We never taste it.

We only smell it.

And it works.

We are both losing weight on our “marmalade” diet.

Which proves, I think, that human beings can survive just about anything—war wounds, poverty, age—so long as there is ritual, memory, and the faint illusion that something sweet is still coming.

The trick, I’ve learned, is not eating less.