W…ritten by

jaron summers © 2026

By the time Isaac Newton had reached middle age, England already suspected it was living in the presence of something rare. He was not charming. He was not generous with credit. He did not laugh easily. He never married.

But he could do something no one else could: he could look at the heavens and reduce them to sentences that did not lie.

Newton was a man of terrifying focus. When a question seized him, it did not loosen its grip for years.

He worked alone, often in silence, inventing entire branches of mathematics because the existing ones were insufficient to express what he saw.

He believed the universe was lawful, ordered, and intelligible—and that it had been designed that way deliberately.

This belief gave his work an almost religious intensity. He was not discovering laws.

He was uncovering God’s handwriting.

Yet the same mind that could unify gravity and motion was also deeply peculiar.

Newton hoarded his ideas. He delayed publication out of fear—fear of criticism, of theft, of being misunderstood.

He held grudges with a patience that bordered on the geological. He suspected betrayal where none existed. He could be generous in theory and merciless in practice.

He did not cultivate intimacy. He lived as if the ordinary requirements of companionship were inefficiencies he could not afford.

And still, for all his brilliance, Newton was drawn to ideas that even his admirers preferred to forget.

He spent decades on alchemy.

He searched for a universal solvent—a substance capable of dissolving anything—without asking the most obvious question: where would you put it once you had found it?

He believed lead could be transmuted into gold, not metaphorically but literally, as though nature itself were merely unfinished craftsmanship awaiting the correct nudge.

He speculated about elixirs of life, convinced that decay was not inevitable but merely misunderstood.

These were not youthful distractions. They persisted alongside his greatest achievements.

The same man who could calculate the motion of planets spent long nights inhaling mercury fumes, convinced that salvation—material, spiritual, or both—was just one refinement away.

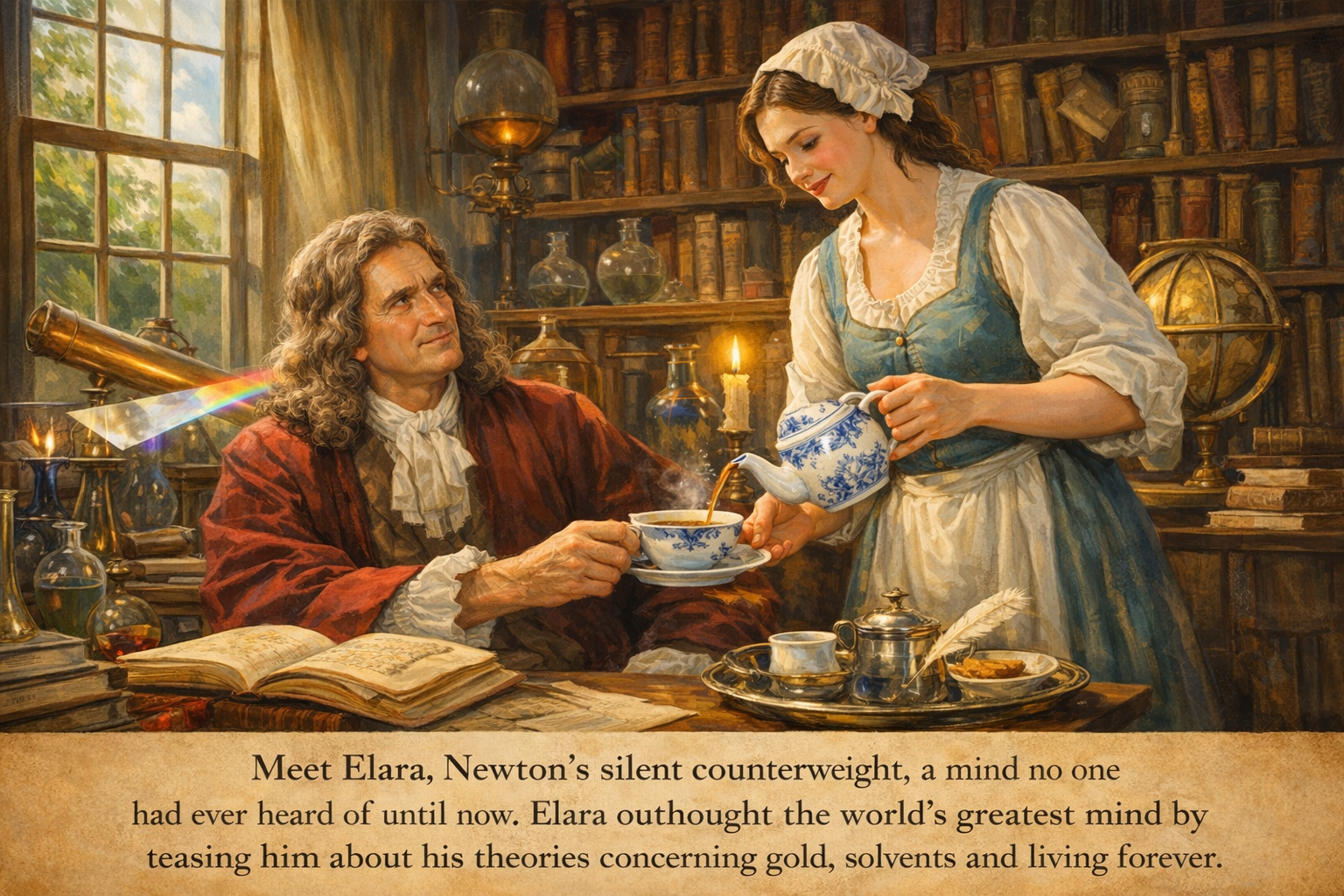

It is here that she enters.

She came to him under a name that was not her own, from a country Newton never visited and barely thought about.

On paper, she was an indentured servant, acquired through channels respectable men did not discuss.

In practice, she was his housekeeper, his assistant, his invisible infrastructure. She prepared meals, tended fires, cleaned glassware, and listened.

She listened constantly.

Newton never asked about her education, which was his first mistake. He assumed—without malice, simply habit—that intellect announced itself. He did not imagine it could hide deliberately.

She spoke little at first. When she did, her English carried the faint geometry of another grammar beneath it.

She asked careful questions. She remembered everything. She read when he slept.

It took him years to notice that she never misused a word.

When Newton spoke of the universal solvent, she did not laugh. She waited until he had finished, until his argument had arranged itself into something he believed complete.

Then she said, gently, as if commenting on the weather, “If it dissolves all things, sir, then it dissolves the vessel that holds it.”

He frowned. He had considered this, of course. He said so. She nodded, as though conceding a point that did not matter.

“And if you solve that,” she continued, “you have not discovered a solvent. You have discovered an ending.”

That unsettled him more than her words should have.

When he spoke of turning lead into gold, she did not object on moral grounds. She objected on economic ones.

“If gold may be made at will,” she said, “then it ceases to be what you value in it. You do not want gold. You want scarcity.”

Newton bristled. He explained refinement, purity, natural ascent. She listened, then said, “If perfection can be manufactured, it will no longer be revered.”

He disliked how often her objections were not technical but structural. She did not argue within his systems. She questioned whether the systems deserved to exist.

The argument over eternal life lasted weeks.

Newton believed life could be extended indefinitely once decay was properly understood. Death, to him, was a mechanical failure.

She asked how long a proof would take. He said centuries, perhaps. She smiled, just once, and said, “Then it is not knowledge. It is faith wearing a laboratory coat.”

That remark cost her three days of silence.

But she had learned the rule that mattered most: she never needed to win outright.

She needed only to leave something unresolved. Newton could not tolerate loose ends. He would worry at them long after she had returned to her work.

He began, slowly, to test his ideas against her absence. He noticed that when she was away, his arguments felt less stable. When she returned, he found himself explaining things he had once assumed were self-evident.

He never acknowledged what she was.

In public, she remained invisible. In private, she was tolerated. In thought, she was unavoidable.

She understood something that one of the world’s smartest man did not: that intelligence without restraint devours itself.

That some questions are not unanswered because they are difficult, but because they are malformed. That the desire to conquer nature often disguises a refusal to accept limits.

Newton believed the universe could be reduced to laws.

She believed laws could explain behavior without explaining purpose. Between them lay a gap neither could cross.

When Newton died—rich, honored, monumentalized—she was not mentioned. No papers record her departure. No letters acknowledge her influence. History does not miss what it never learned to see.

But if genius requires friction to spark, then Newton did not work alone.

He sought to turn lead into gold, to dissolve the world, to outrun death itself. She sought only to ask whether these victories would survive their own success.

And in that difference—quiet, unrecorded, and decisive—she may have been the wiser mind. Her name was Elara.

Author’s Note

Readers may reasonably ask how the figure of Elara entered this account.

In 1967, while serving as editor of The Daily Universe at Brigham Young University, I interviewed and photographed the American playwright Barry Stavis, who was in Utah in connection with a campus performance of his play Galileo. The photographs were later used, with my permission, on published material associated with his work—an anecdote I include only because it is independently verifiable in the newspaper’s archives.

During our conversations, Stavis learned of my interest in screenwriting and encouraged it. In that context, he showed me a handwritten letter attributed to Galileo Galilei, written in Italian. The letter made a brief, passing reference to a woman identified as Elara. No surname was given. No explanation followed.

For many years I believed the letter—like much youthful ephemera—had been misplaced. While reviewing old papers recently, I came across it again. I have not located any secondary historical reference to Elara, nor do I claim the letter alters the established historical record.

The post above this should therefore be read as an interpretation shaped by absence rather than assertion. If Elara mattered to Galileo, she did so quietly—and without leaving more than a trace.