W…ritten by

jaron summers © 2026

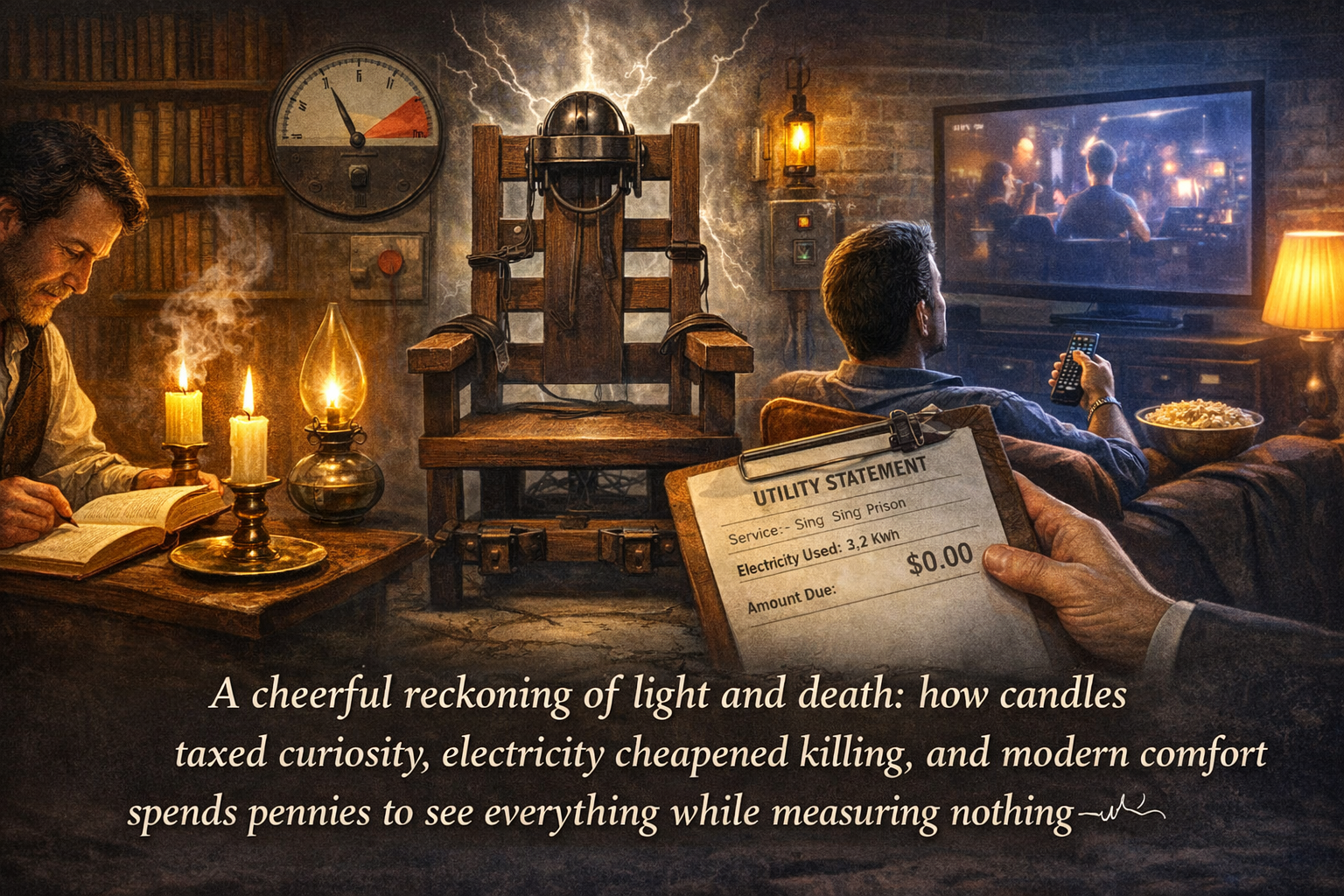

If a man wanted to read after dark in 1825, he had to burn something that had once been alive. This added a moral dimension to literacy. The cheapest option was a tallow candle, made from animal fat and optimism. It smoked, hissed, and smelled like a barn filing for divorce. It produced just enough light to make words visible, though not necessarily wise. Reading by it required posture, patience, and a tolerance for regret.

A beeswax candle was brighter and cleaner. It was also expensive. Lighting one alone was the 19th-century equivalent of ordering champagne for yourself and pretending it was an accident. Oil lamps sat in the middle. Whale oil if you were doing well. Vegetable oil if you were not. Either way, the lamp perched on the table like a small accountant, silently timing how long you lingered on a sentence that might not pay rent.

And that was the real cost. Not the candle. The time. A laborer earned about a dollar a day. A few hours of reading each night quietly consumed a meaningful fraction of that. Every paragraph had a burn rate. Every footnote tasted faintly of tomorrow’s bread. So people read differently. They reread. They memorized. They argued with margins because forgetting was expensive.

This is why libraries were small. Not because people were stupid or incurious, but because curiosity came with a monthly bill and no student discount. A man might own six books and know them like relatives—flaws, virtues, and that one passage everyone avoided at dinner. He didn’t skim. He inhabited. When he blew out the candle, it was rarely because he was tired. It was because he had done the math.

Now let’s jump ahead to electricity. In 1890, New York decided to kill a man using it. This was marketed as progress. The first electric execution took place at Sing Sing Prison, and the selling points were many: modernity, precision, and the comforting illusion that science was now in charge. No ropes. No trapdoors. No embarrassing physics involving gravity and necks. Just a switch.

What nobody mentioned—because it would have sounded tacky—was the price of the electricity. It was almost nothing. An electric execution uses roughly two to four kilowatt-hours of power. That was true in 1890. It is still true now. The electricity required to end a human life cost pennies then and costs pocket change today. Less than a dollar. Often less than your evening snack.

The killing has never been the expensive part. What cost money in 1890 was the chair, the wiring, and the novelty. What costs money now is the conversation. Decades of appeals. Armies of lawyers. Experts, hearings, reviews, safeguards, and procedural solemnity stacked high enough to block the sun. A modern execution costs one to three million dollars more than life imprisonment. The electricity still costs less than running a hair dryer.

Which brings us, gently and smiling, to Netflix. If you sit down tonight and binge-watch a series—big screen, streaming box, router, ambient lighting so you can feel feelings—you will almost certainly use more electricity than the state did to execute a man in 1890. Your evening entertainment will outdraw the electric chair. Netflix will politely ask if you’re still watching. The chair never did.

Electricity used to terrify people. They trusted it anyway. Today it’s so cheap and familiar we leave it running while we argue about morality online, illuminated by LEDs powered by the same grid that once delivered death with ceremonial seriousness. Which leads to the line nobody asked for but everyone earns: The most expensive part of killing a man has never been the power. It’s the paperwork required to feel okay about it.