The Antibiotic Gap

W…ritten by

jaron summers © 2026

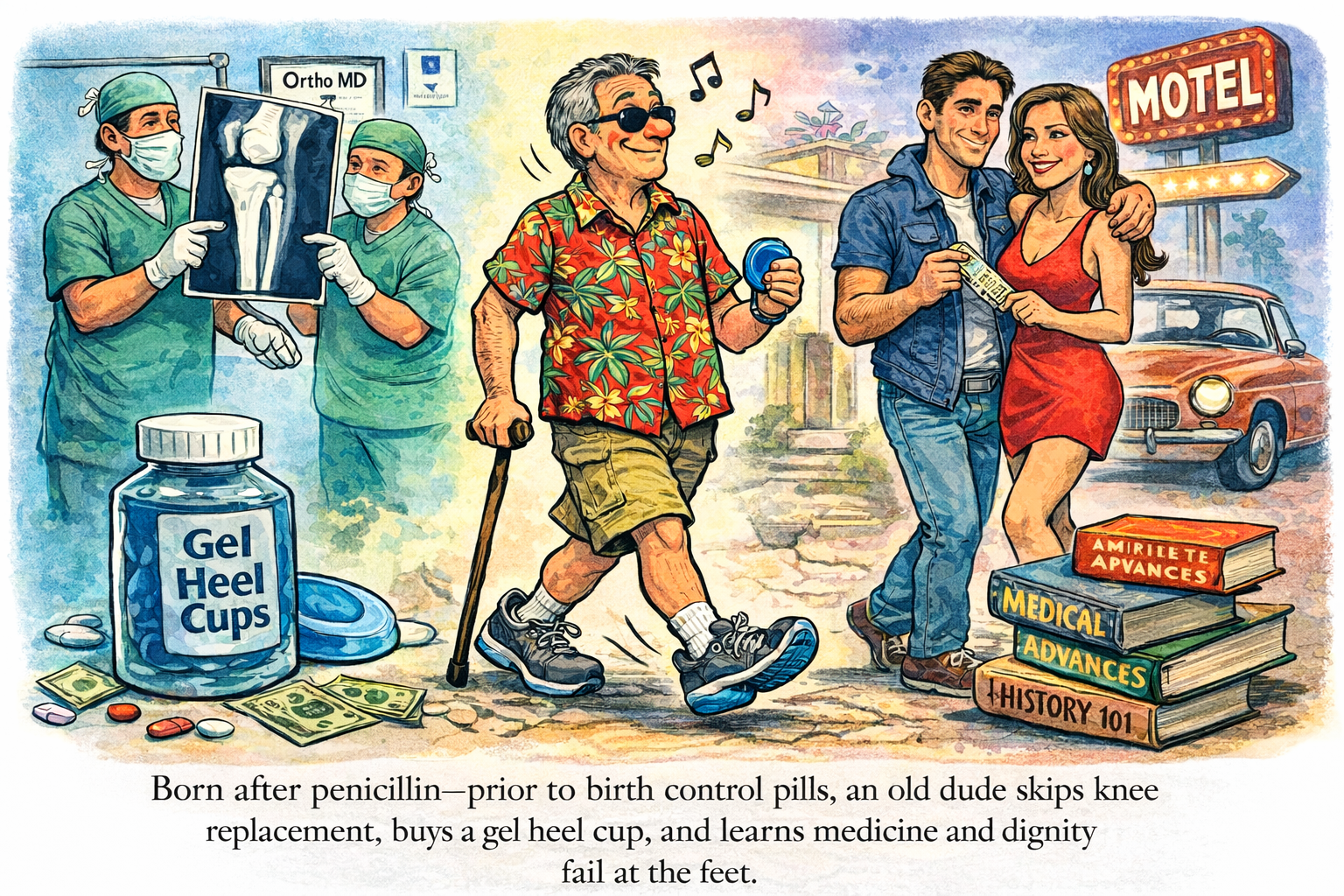

We were born into what I’m calling the Antibiotic Gap—a stretch of history after penicillin but before birth control, when death had learned some manners but sex still carried consequences.

Childhood infections no longer cleared the classroom, yet adulthood arrived without safety rails. You could survive pneumonia, but you could still ruin your life on a Friday night.

It was a small, accidental window, and we lived inside it without knowing it was closing.

Illness still had a voice, but not the final word. Sex was not yet an administrative matter. It came wrapped in secrecy, timing, and luck—like a gift you weren’t sure you were allowed to open.

People got sick, got pregnant, got married, disappeared, or didn’t—and nobody pretended these outcomes were interchangeable.

Progress existed, but it had not yet been padded.

The Pill arrived just late enough that we learned desire before protection, and medicine arrived just early enough that we lived to remember it.

We were trained—without instruction—to understand risk as something negotiated rather than eliminated. Survival improved faster than behavior adapted.

The body became survivable but not negotiable. Consequences remained intact.

That early education lingers. It shows up later, in money, love, and especially medicine.

We do not assume rescue. We listen. We bargain. We notice when something works too fast to be a miracle.

For the better part of a year, I limped. My heel hurt. My back ached. My knees complained in a steady, pessimistic tone.

A couple of doctors—after what I can only describe as a wallet biopsy—concluded I needed knee replacements.

This was said with confidence, charts, and the calm authority of men who had already mentally parked my car.

Instead, I bought a small gel heel cup—the sort of object sold near the pharmacy register, just below the dignity line.

Within an hour, my back pain was ninety-eight percent gone. The limp vanished. My heel stopped protesting.

When I sat, the pain disappeared entirely, as if embarrassed to have been misattributed.

Nothing structural heals that quickly. Muscles do. Alignment does. Physics does.

The body, it turns out, is less impressed by credentials than by leverage. It does not care what your surgeon drives.

This was not a miracle. It was penicillin logic applied late: find the actual problem, interfere gently, and stop when the symptoms retreat.

It felt oddly familiar—like learning again that medicine works best when it’s not trying to save your life, just your afternoon.

People born after the Gap often experience medicine as a subscription service.

There is an expectation of escalation. If something hurts, it must be replaced. If a system falters, it should be bypassed.

We came up differently. We assume medicine helps, but we don’t assume it finishes the sentence.

We know relief can be provisional, local, even cheap.

We have seen outcomes hinge on timing, not technology.

The same instincts govern how we live.

My wife and I earn a modest, predictable income from pensions and Social Security. We don’t spend all of it.

Some of it goes back into the market, quietly compounding—unglamorous and patient, like a sensible dog.

We have excellent healthcare through the Writers Guild.

We travel cheaply because she retired from United Airlines back when flight attendants still spoke with authority and people occasionally behaved in public.

We help friends. We keep younger people in our lives.

None of this feels like optimization. It feels like insurance learned early—the emotional kind, not the actuarial.

We were never taught that safety was automatic.

Only that it was possible—and unevenly distributed.

Sex before the Pill taught us that desire could be joyful and dangerous without being tragic.

Antibiotics taught us that death could be delayed without being abolished.

Money, later on, felt similar. You could survive mistakes, but only if you noticed them in time.

The culture moved on. Risk got padded. Consequence got outsourced.

Sex became safer, then safer still. Medicine grew bolder. Surgeries multiplied.

The body became something to be upgraded rather than listened to. None of this is wrong.

It’s just different.

People raised with airbags drive differently than people raised with seat belts and prayer.

Those of us from the Antibiotic Gap still flinch a little at certainty.

We respect progress, but we don’t confuse it with immunity.

We know systems fail quietly before they fail loudly.

We know relief that arrives instantly deserves curiosity, not gratitude.

And we know that sometimes the smartest intervention is not heroic, but humble—a pill that works, a cup of gel, a pause before agreeing to be rebuilt.

We were born at the right time by accident.

Late enough to live. Early enough to remember why living mattered.

A Few Practical Questions

What heel cups did you use?

They are Homergy Heel Cups. I bought them on Amazon. They cost between seven and twelve dollars, depending on quantity and the algorithm’s mood. I have no connection to the company. They simply worked—for me.

Did you follow instructions?

No. There was a QR code with directions. I ignored it, put them in my shoes, and walked. The effect was noticeable within an hour.

Did the heel cups cure anything?

No. They changed how my body bore weight. That alone relieved pain that had been blamed on my knees and back.

Does this mean knee replacement isn’t necessary?

No. Knee replacement can be essential. This is only a reminder that knee pain doesn’t always start at the knee.

Is this medical advice?

No. It’s personal experience. But if a small, reversible change alters symptoms quickly, that information may be worth having before making a permanent decision.