W…ritten by

jaron summers © 2026

When I, at the age of seven, arrived in Coronation strange things began happening to me. This was unfortunate, as I was not prepared for them and had not been consulted.

I knew no one. I missed my friends in Victoria, British Columbia. I longed for the Pacific Ocean, which had been a dependable companion and rarely tried to kill me. We lived at the end of Government Street, only a few hundred feet from the sand and the driftwood I rediscovered each morning like a personal museum that refreshed itself overnight.

I had seldom seen snow, which until then I regarded as a rumor spread by eastern Canadians.

We arrived in Coronation—population 950, every one of them alert—at the end of a two-day drive. My father, freshly installed as the town dentist, could find only one place for us to live. It was an abandoned beauty salon with a large picture window, clearly designed to display hairstyles rather than families, but adaptable in emergencies.

On my first school morning, my father woke me early. I blinked and told him it was still dark.

“We had a little snow,” he said.

Little? The picture window was completely buried—three or four feet thick. The world had been erased overnight, as if God had decided to start again and forgotten to leave instructions.

We dug our way out and I trudged to school, where I met the other children—about thirty of them crammed into one room covering grades one through three. This arrangement saved money and ensured that no child escaped educational trauma.

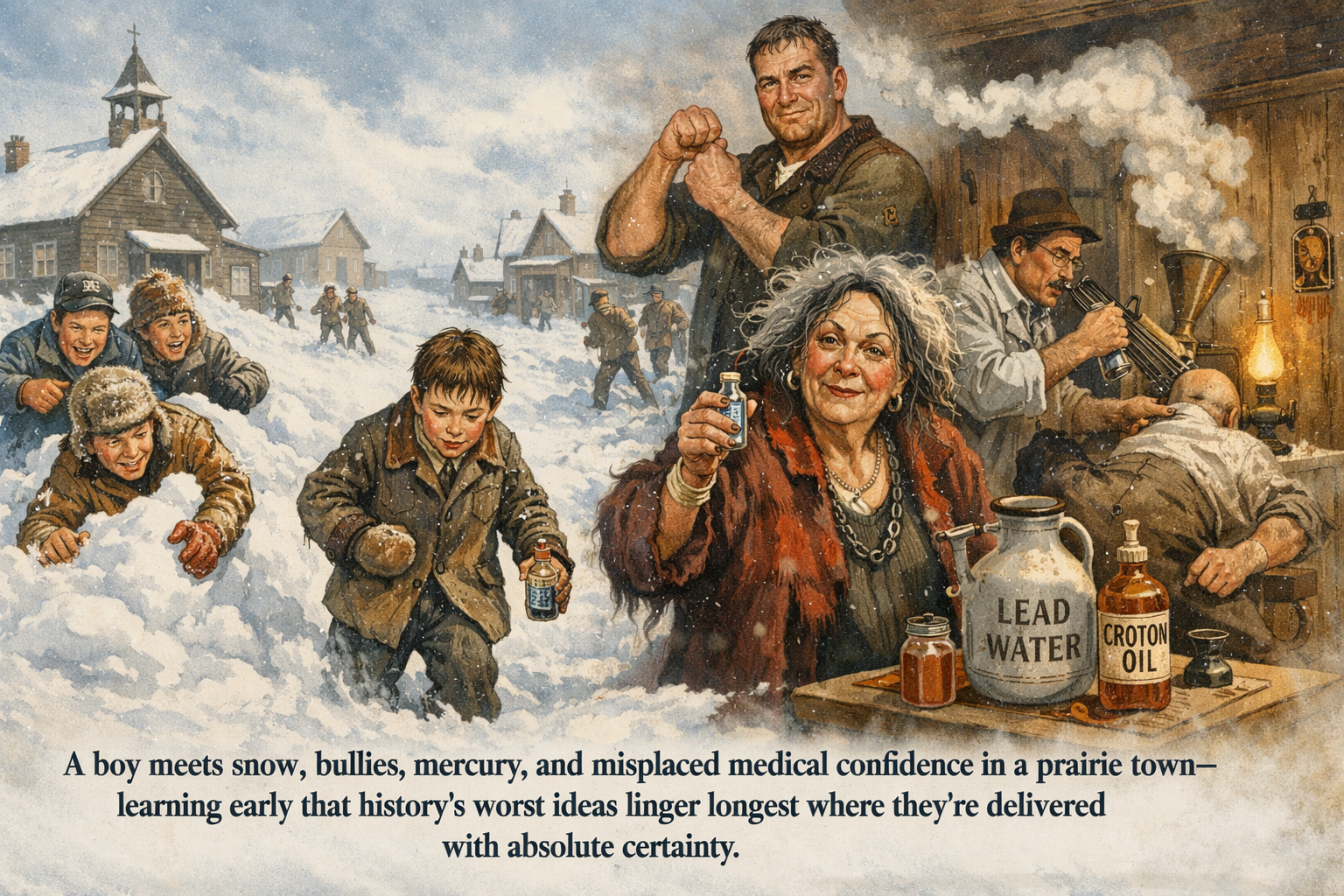

By Monday afternoon, the local bully had pushed me into a snowdrift and laughed. By Friday, I had been boxed around, had my mittens stolen, and learned that cruelty travels faster in small towns because it has nowhere else to go. One boy said he liked my new shoes and stamped on my right toe. There went the shine. Hello, lifelong memory.

My parents, I later learned, were already wondering if the move had been a terrible mistake. They thoughtfully decided not to tell me. I overheard enough to conclude that my life was effectively over and would now consist of snow, pain, and dental instruments.

That Friday afternoon, walking home alone, I sensed someone behind me.

An old woman with wild hair and half-applied lipstick appeared to trail me. I sped up. She sped up. I cut between two busted wooden buildings, believing I had discovered a clever shortcut.

She had discovered it first.

As I emerged into the bright sun, she seized me by the ear with professional assurance. She already knew who I was—the new dentist’s son—and she informed me that she would give me a quarter if I brought her some mercury.

“My dad says not to go near it,” I said, invoking authority as one does when cornered by madness.

“Your dad might be some hot shit dentist from the coast,” she replied, “but he knows nothing about BMs.”

I did not know what a BM was. She explained it thoroughly, graphically, and without mercy.

She vowed that her six-foot-two son would kick my ass if I failed to accommodate her medical needs. She added her large son would love to rip off one of my parents’ heads and take a BM in it.

At seven years old, faced with science and violence, I made the only rational choice.

I liberated some mercury—night-night, we called it—from my father’s lab and delivered it the next morning.

The explainer of all things constipated became my only friend, provided I maintained her supply of lethal mercury.

Her son later thanked me and offered to help with my homework for twenty-five cents an hour. This was my first experience with outsourcing education and protection.

It would take years for me to understand how perfectly normal this arrangement was, historically speaking.

A Final Note From the Author

You may be wondering why I seem to have wandered from mercury and its dangers.

Simple.

The Dark Ages were still happening in Coronation in 1950. Tobacco smoke enemas. Lead water. Croton oil. Medical certainty delivered with confidence and no refunds.

I had not moved to a town.

I had moved into a museum.

Brimming with ancient dangers.

Say tuned.