Because public attention is a finite resource, political crises have a way of obscuring and supplanting one another. On the morning of November 2nd, New York City’s mayor, Eric Adams, flew to Washington, D.C., for a full day of meetings about New York’s migrant crisis. “We are headed to D.C. to meet with our congressional delegation and the White House to address this real issue,” Adams said in a video posted on his X account at 7:41 a.m. “We’ll keep you updated as the day goes on.”

For more than a year, without much success, Adams had been calling on the federal government to defray the astronomical costs of housing tens of thousands of immigrants in city-run shelters. He had gone as far as suggesting that without federal help the migrant crisis would “destroy” New York. Though the dispute had damaged his public relationship with President Joe Biden, the Mayor was getting an audience at the White House. But Adams never made his meetings. That same morning, news broke of an F.B.I. raid at the home of one of his campaign fund-raising officials, Brianna Suggs. Already on the ground in D.C., Adams caught the first plane home, in order to “deal with a matter,” as a City Hall spokesperson put it.

Suggs, who is twenty-five, lives with her father and grandmother in a row house in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. She graduated from Brooklyn College in 2020, and she served on Adams’s 2021 mayoral campaign as a fund-raiser and “logistics director,” according to her LinkedIn page. At Suggs’s house, federal agents reportedly confiscated two laptops, three iPhones, and a manila folder labelled “Eric Adams.” The Times reported that the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan is trying to determine whether representatives of the Turkish government illegally funnelled money into Adams’s campaign.

Back in New York, Adams avoided reporters, and put off public appearances. News outlets began combing through his campaign-finance records, paying close attention to the fourteen thousand dollars in donations made by employees of a Brooklyn construction company reportedly owned by Turkish New Yorkers, and to the ten thousand dollars in donations made by employees of a small private university with ties to Turkish institutions. Adams is not the world’s most disciplined public speaker, and City Hall reporters have learned to take him seriously, if not always literally. (“Adams doesn’t just polish anecdotes,” my colleague Ian Parker wrote in a profile of Adams earlier this year. “He is unusually ready to repeat things that are confirmably untrue.”) Yet some of his former statements, particularly those regarding Turkey, took on a newfound significance after the raid. “When I get elected, you’re going to have your first Turkish Mayor,” Adams once told a Turkish American business news Web site. “The Turkish community has really supported and held several fundraisers for me. I’m extremely appreciative of the substantial dollar amount they have.”

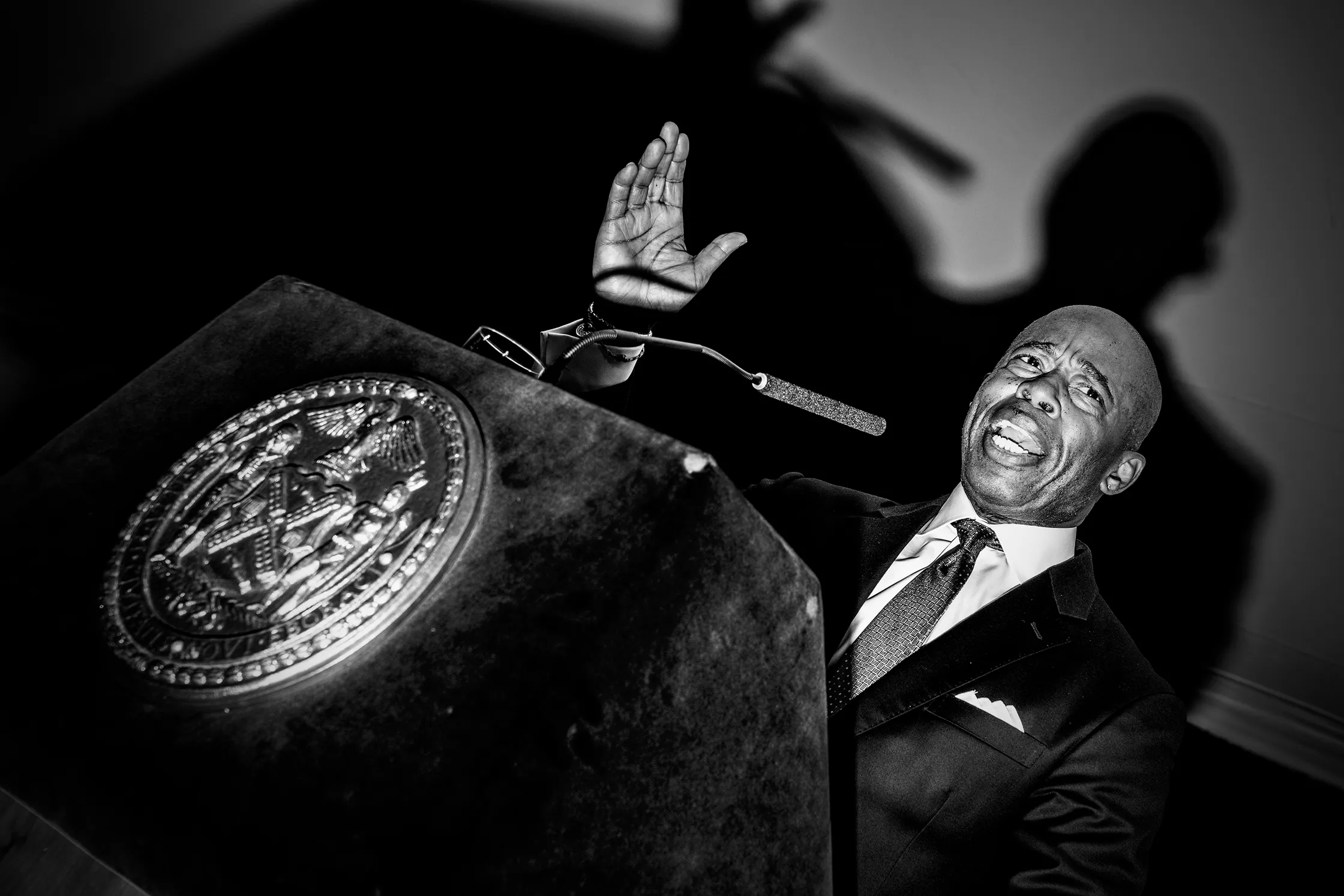

Six days after the raid, Adams convened a press conference to address what was going on. He told the assembled reporters that he wanted to be “completely transparent,” and then refused to detail what exactly he had done or whom he had spoken to after returning from Washington. “I did not want to be sitting inside a meeting somewhere when there was something playing out here in the city,” he said. When asked if he was worried that he himself might face criminal charges, he laughed. “I would be shocked,” he said. “WilmerHale . . . that’s the law firm that I’ve retained . . . they are professionals in this area.” He insisted that, as a former police captain, he knew right from wrong. “I cannot tell you how much I start the day with telling my team we’ve got to follow the law,” he said. “Almost to the point that I’m annoying.” Here was a new crisis for the city to grapple with: Could the Mayor be believed?

For years, Adams’s critics have been predicting that a corruption scandal would do him in. Many aides, allies, friends, and associates of his have been investigated, and some indicted, for a range of frauds and bad acts in office. He’s generally stuck by them, valuing loyalty over any other political consideration, even at the risk of appearing personally compromised. In July, the Manhattan District Attorney brought campaign-finance charges against several donors to Adams’s 2021 mayoral campaign, two of which have pleaded guilty. Adams waved it off, saying he was totally uninvolved. “I follow one rule: follow the rules,” he said. In September, his former Department of Buildings commissioner, Eric Ulrich, was indicted on allegations of favor trading and bribery. According to the Daily News, Ulrich, who has pleaded not guilty, told investigators that Adams had warned him to “watch your back and watch your phones.” Adams denied saying this. He has long suggested that he faces more scrutiny than other politicians because he is Black. “My face will show up on front pages of, ‘Is there unethical and immoral behavior?,’ ” he said last week, speaking to a Brooklyn church congregation three days after the F.B.I. raid. “We’re going to be all right.”