I might live to be a hundred he says. “But then again, there’s a chance I won’t.”

He taps a cigarette from a pack and touches a match to the tobacco and inhales deeply.

Now in his 81st year, Doug Paul, M.D., contemplates death, something — he, as a medical doctor — has battled against all of his life. Until recently that battle has been fought on behalf of others.

After a lifetime of service to his country and community, Dr. Paul is, to use his own phrase, “on his last legs.” He uses a cane to get around and has taken a few severe tumbles. “I’ve had more operations than a fried cat.”

He wears a “Life Alert” medical device around his neck and with it he can summon help via a telephone if he falls and can’t get up.

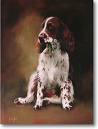

He has had to use it several times but it allows him to live alone and he is fiercely independent. In truth, he is not alone for he shares his three-bedroom home and large backyard with Ben, his English springer spaniel of fifteen years.

“If you’re going to get sick in Alberta, don’t be a dog. Dogs can’t afford the vet bills. Neither can their owners,” he says.

“Vets charge far more for their services than I ever billed any human patients for mine.”

During over 40 years of medical practice, Dr. Paul always sported a mustache.

Because of shingles that cause him considerable pain, he has stopped shaving altogether and has a luxurious brown beard spotted with twists of grey.

Because of a stroke, his left hand is almost useless but he can still drive a car. He has a sporty four door blue station wagon with a special cage for his beloved Ben.

Dr. Paul is a diabetic and takes insulin daily. In addition to this, he must use numerous pills to supplement his weakening, and in some cases inoperative, organs.

Sugar is verboten, however, he occasionally sneaks a chocolate.

“Half my major arteries have been rewired and pieces of me are falling off,” he says with the wry observation of a physician and philosopher. “I’m about two to a hill.” (This is a Maritimes expression to describe a poor crop of potatoes, most hills should have 20 or 30 spuds in them.)

“I wish I had been this sick when I was younger,” he says. “That way I could appreciate what my patients had to go through.”

Not long ago, Dr. Paul’s daughter, Heather, 54 (a schoolteacher) drove him to Didsbury where he purchased a cemetery plot for himself and his wife, Cille.

She died ten years ago. Dr. Paul has kept her ashes and when he dies, he too will be cremated and their ashes will be buried in Didsbury.

“It’s a lovely cemetery and the plots are only $200. Why anyone would want to spend five or six thousand for a plot in Edmonton — why that’s just crazy.” The granite headstone, which will bear his and his wife’s name, costs $2000.

Didsbury has changed so much over the last 30 years that he hardly recognizes it.

Only one or two of the old landmarks are there. The town was one of his favorite places — a thriving community, only a few minutes ride to fine duck and upland game hunting.

Such memories.

The gleaming tracks of the railway glide through the center of Didsbury. If those steel tracks could talk they would tell a story about the time a man was killed on those rails and a young country physician, Dr. Paul, instructed the RCMP to record the skid marks of the great coal-driven locomotive.

After the skid marks were measured, the physician had the police carefully interview the people and crew on the train.

“And while you’re at it, boys,” he said, “measure the circumference of all the wheels on that death train.”

This ate up time and played havoc with the CPR train schedule across Canada.

The executives of the railway issued stern warnings to Dr. Paul and the warnings turned to threats.

In those days the local coroner had tremendous power. And in addition to being the local country doctor, Doug Paul…was the coroner.

And then someone remembered that Dr. Paul had saved the arm of a CPR employee and, since the operation had taken three times as long as the CPR had thought was necessary, there was a dispute over the bill.

The CPR’s lawyers had gotten into the act and had written a note to Dr. Paul saying that the company — which was all powerful — would not pay the bill. They were quibbling over thirty or forty dollars.

With rail service halted across Canada, the bill was quickly paid and lo and behold, the train in Didsbury that was disrupting the nation, pulled out of the station.

Such memories.

But of course the tracks of 1997 cannot talk.

Still, for Dr. Paul, Didsbury will always hold a special place in his heart.

The people. The patients. The hunting.

Ah, the hunting….

That’s all over now. “I stopped hunting with friends five years ago because I was afraid I’d end up shooting one of them. And then I stopped hunting altogether because I was afraid I’d end up shooting myself or my dog.

One gets the impression he was more worried about killing his dog than himself for he is not afraid of death. He has been around it too many times. He watched a lot of men die in World War II.

He watched a lot of elderly and even the young die. He calls pneumonia “the old peoples’ friend” and says it’s one of the most pleasant ways to depart this earth.

As a young medical doctor he joined the Canadian army and found himself on a troop ship to England. Half way across the Atlantic, a sailor ruptured his appendix and Dr. Paul began emergency surgery.

The ship, plowing through a great storm, tossed so violently that the sailor kept sliding away from the young doctor.

The young doctor sent an urgent request to the captain to stop the ship for 15 minutes or the young sailor would die.

“Then die he must,” said the captain, “if we dare to slow this ship now, a German U-boat will blow us out of the water.”

These were the days of the infamous Nazi wolf packs.

“I somehow sliced open the sailor, removed his appendix and sewed him up successfully, no thanks to the captain,” says Dr. Paul.

The next day one of the boilers on the ship broke and the vessel drifted helplessly on the high seas for six hours.

Fortunately there were no enemy subs in the area. “Or if they were,” he says, “They were busy sinking other ships.”

Perhaps it was in the war where Dr. Paul learned to break the rules.

He and another medical doctor were smuggled into Holland before it was liberated. Their assignment was to set up a mobile field dressing station in the midst of the enemy. This would be to prepare for the upcoming battle (that they didn’t know was coming.)

Dr. Paul surreptitiously put together the hospital unit.

Nearby he discovered the small city of Eindhoven with a make-shift hospital for kids who had been wounded in the war.

He secretly transported medical supplies to the hospital.

The problem: there was no doctor there to operate on the kids. Dr. Paul rolled up his sleeves and went to work. A week later, about fifty kids were alive who would have been dead.

The Nazis and Dutch sympathizers swarmed all around him. If the Canadian military had found out what Captain Paul was up to, he would have been court-martialed. Medical supplies were sacrosanct and were only for the troops.

In his home, near the University of Alberta, there is a small bronze plaque in Dutch that the children presented to him over half a century ago during the second Great War.

Dr. Paul did not see his wife for four years during that war and the endless hours in surgery took their toll on the young medical doctor. Sometimes he would be in surgery for three days non-stop. He saved a lot of lives —

Even in the midst of battle there was some respite and some humor. He recalls billeting with a padre as war was coming to an end near Holland.

They slept in a tent and one night, Dr. Paul heard sounds in the darkness. “In those moments you took aggressive action,” he says.

“I walked out of the tent and emptied my handgun in the direction of the sounds — we knew no one would approach without identifying himself. Well, the padre gave me hell for such reckless behavior.”

“The next night I was awakened at three AM by the sounds of gunshots. It was the padre, standing outside the tent, emptying my handgun into the darkness. Apparently he had heard sounds.”

And there were excursions to his homeland in Scotland. “We stayed at a delightful little hotel. They had no provisions and the next morning they asked us what we wanted for breakfast.

As a joke we said thick bacon and eggs. Of course there was no bacon to be had in Europe. Magically the bacon and eggs appeared.”

And then there was the time after the liberation that the European women had to sell themselves to the troops so they could buy food for their kids.

The currency was cigarettes. Dr. Paul and his friend the padre “liberated” hundreds of cases of cigarettes and gave them to the women. That put a stop to the prostitution.

He has a few other memories of the war in his home. There is a photo on the wall of the house in Scotland where his mother was born in the 1800s.

In his kitchen is a microwave oven where he does most of his cooking. Until his children presented him with a microwave he was dead set against it, preferring to make his meals the natural way. “By burning them on the stove.”

Every month, he hires a group of house cleaners to attack his place, the rest of the time he manages to keep it reasonably clean on his own. He hates washing and it seems to pile up faster than he can handle it. Part of this is because he is meticulously clean.

It’s part of a medical background. He graduated with a M.D., C.M. from Queens in 1942. His anatomy instructor told the class at the beginning of the session that in order to pass they would have to know everything in the textbook.

A year later, the instructor asked Doug, what he knew about the textbook. The cocky young med answered “everything.” Apparently that was the right answer for Doug Paul graduated with honors.

Dr. Paul is amused by today’s medical specialists and their narrow focus of expertise. In his day, Dr. Paul, treated the entire patient. Actually, he treated more than that, he treated the entire community.

He spent twenty years in Didsbury (just north of Calgary) and knew everyone there. And everyone knew him. He also practiced in nearby Carstairs.

Bright, complex, sarcastic (he does not suffer fools — be they patients, family members or hunting companions), Dr. Paul ended up saving a lot of lives.

Yet, now in an age of political correctness, Dr. Paul is a dinosaur.

He refers to nurses who make errors as “misguided girlies.” He tries to bridle his contempt for inept medical practitioners.

Referring to a doctor who is not high on his list of competence he simply says: “So and so had the misfortune to fall under Doctor X’s scalpel.

Just as Churchill was the right man for the right job at the right time, Dr. Paul was once the right man for the right job.

That job was the creation of a health care system.

When the social credit government was searching for a man to create Alberta Health Care in the early 70s, they needed a rare combination of talent.

First he had to be a medical doctor to appease the medical community.

He had to be a leader. A visionary. It was essential the person understood bureaucracy and how to deal with it. Perhaps someone in Ernest Manning’s government read some of the letters Dr. Paul had written criticizing it.

Besides being a superb physician and surgeon, Dr. Paul is a master of the English language and he simply does not make errors in grammar.

The last thing Manning needed was a yes man, but mostly what was required was a man who would implement the definitive program that would help Albertans.

Bottom line: in addition to all of the difficult attributes the successful candidate had to have, he would have to love Alberta and its future.

The short list was pretty short.

When Manning saw it, he placed Doug Paul, M.D., in charge of what was to become Alberta Health Care and is now known as Capital Health Care.

Dr. Paul was given the signing authority of a minister (read: he could write a check for any amount of money and the Alberta Government would have to honor it) and told he had four months to bring Alberta Health Care on line.

Dr. Paul decided to use computers and his ideas cut deep into cyberspace, a word and concept which was unknown to 99.99 percent of the world.

In Dr. Paul’s vision of the perfect health care system, everyone in Alberta would be looked after. There would be no fees paid by the patient and the only way one could see a specialist would be through the referral of a family doctor.

Manning balked at this. He wanted “user fees,” albeit tiny ones. Perhaps it was his way of reminding Albertans that with a small check several times a year, they were getting the best health care in the world. In those days this province was afloat with money. Oil money that would generate a boom like Canada has never seen.

There were other things Dr. Paul suggested. Simply by scanning your Alberta Health Care card through a reader, a doctor would immediately have all your vital statistics and medical history. The powers that be thought that was a bit too invasive of the voters personal rights. Never mind that it would save lives.

There were compromises but in the end Dr. Paul created the finest health care system that Canada and perhaps the world had ever seen. He won a few bets too. A case of whiskey from one of the executives of TransAmerica Corporation who said that the health care system would cost more than 7 percent to administrate.

It was a tremendous challenge, however, the young medical student from Queens, who fought in World War II, hunted wild geese and enjoyed canoeing the hidden northern lakes of Alberta, was worthy of the challenge.

For a shining decade after that Alberta had a health care system that was the envy of the world. The Camelot of Medicine.

But Camelots have a way of disappearing.

Today Dr. Paul is not pleased with what he calls “the beer hall politics” of Alberta’s Ralph Klein and the way the medical care program of Alberta is being torn apart by short sighted politicians.

In talking with Dr. Paul, it’s obvious that he cares about medicine as much as any Canadian.

His record speaks volumes. It is not the record of a specialist or a “modern doctor.” It is the record of an old fashioned country doctor, that a world war tested. It has made Dr. Paul a national treasure.

He delivered over 2,000 babies and never lost a mom. He knows a special technique for rotating a baby around in the birth canal if it’s going to be a breach delivery. Most obstetricians of today, faced with such a challenge, perform a Cesarean.

Dr. Paul scoffs at the many Caesarians that are done and considers most of them unnecessary and nonsense.

He himself would be the first to admit he is a strange meld of ethics. He has never performed an abortion unless the mother’s life was in danger.

He says he cannot count the number of times women begged him to terminate their pregnancy but he couldn’t do it.

They always thanked him afterwards for a healthy son or daughter.

“In my day, if a child was born with a serious disease, and there was no hope of that child having a life — we simply set the child down and let nature take it. We didn’t practice heroics.

“I suppose I shall be judged someday for what I did. In my day, it was a different kind of medicine.

“Now you have lawyers in the hallways.”

In his day the physician understood the disease, the person and the community.

Doctors did things differently. People were not numbers. They were the sons and daughters of friends. The country doctor knew the history of the patient before she ever came into his office.

And the doctors did things differently in the old days.

“If someone has a heart attack and you want to kill him, call 911 and load the poor bastard into the back of an ambulance and then, with sirens screaming, rush him to the hospital. If the coronary doesn’t kill him the ride will scare him to death.”

Possibly this is how Dr. Paul managed to have one of the highest survival rates for heart attack victims.

“Really quite simple. I got to the patient as fast as possible, shot him full of morphine and made him stay in bed. The morphine was to stop the pain and it did a wonderful job. Then on the third or fourth day, I’d quietly move the patient to the hospital where I could monitor his recovery.”

And when it came to curing the simple cold, Dr. Paul came pretty close. His cough syrup could stop a cough almost instantly.

“It’s so simple it’s ridiculous,” says Dr. Paul. “There’s no money in something that easy to make and the big drug companies can’t make a cent out it but it stopped thousands of babies from crying their heads off and never harmed a one of them.

Dr. Paul weighs exactly what he did after he came out of the army:140 pounds. The last five years have been near murder on him.

Strokes, emphysema and coronaries have knocked him down again and again. He carries on—thanks in part to being a recipient of what’s left of the superb health care system he pretty much created single handedly.

He drinks single malt Scotch. “Perhaps a bit too much and I smoke. I’ve tried to stop a thousand times. I can’t and that’s what will probably kill me.”

He started at the age of eight and his father (a banker in Saskatchewan) walked by and saw him.

“I was afraid I would get a whipping that night but by my dinner plate there was a pipe. My father said if you have to smoke, smoke like a man.”

Although Dr. Paul stopped hunting for fear he might end the life of himself or his friends or his dog, he probably hung up his rifle for other reasons. “I shot a coyote and it just jumped up in the air and died and after that I just didn’t want to hunt any more.”

Before that the doctor lived to hunt and fish.

He was particularly fond of goose hunting that he did in the Coronation district. He often finished surgery in Didsbury at five in the evening, then drove with Taupe, a huge Weimaraner, until midnight to reach Coronation, the home of the Canada Goose on its winter migration to Florida and The Gulf.

Friends would have scouted the location of the geese and then at four AM, Dr. Paul would get up and drive 30 minutes to where he and his friends would dig goose pits and wait for the geese.

Taupe was great for bringing back the geese that fell from the sky when Dr. Paul nailed them with his .16 gauge Browning.

Taupe was also a terrific pointer when it came to pheasants but if he found the birds and Dr. Paul missed the first three shots, the Weimaraner would give up hunting for the day.

Around Coronation in October when the “geese were running” the air was so cold in the early mornings that Dr. Paul and his friends could not uncap the tops of mickeys so they would have to do without a drink until sunrise, at which time the geese would—if the hunters were lucky—return to the wheat fields.

Guess who they took along to open the booze? Me. Although I was not allowed to taste it. That is where I learned how to hunt Canada geese.

In Didsbury, over the years, Dr. Paul bought several homes, one of which had an acreage with a barn. Here he bred Weimaraners and chickens.

Over the barn door hung a large elk head he had taken. The moose had charged him and he had barely been able to get to his gun before it would have killed him.

There was a gravel road that ran by his acreage and often speeders disturbed his Sundays. On these days he instructed his children and their friends to construct what he called “beaver dams” across the road. This usually slowed down the speeders.

He himself liked to speed and justified it since he was often on the way to an emergency. Once in Saskatchewan an RCMP officer stopped him for speeding.

“I note,” said the officer, “that you are a medical doctor.”

“Yes,” said Dr. Paul.

“And I suppose you are on your way to an emergency.”

“To tell the truth officer, I am not. I’m coming home from a wedding.”

“Then,” said the RCMP officer, “I won’t give you a ticket since you are the first doctor I have stopped in my life who was not on his way to an emergency. Carry on.”

Dr. Paul knew the backwoods of Canada as well as any man and chose to use them instead of the main roads (much to the horror of his wife and his family).

He often drove a four-wheel Travel-all with a winch and they said he enjoyed getting stuck, then directing the family on the uses of the winch.

He, of course, seldom got muddy because he had to drive.

Once in the backwoods he drove past a Hutterite colony. They stopped him and explained that one of their horses had been injured in a Texas cattle gate—a series of iron bars buried in the ground.

Dr. Paul examined the animal. It had several compound fractures and there was no alternative but to put the poor creature out of its misery.

No one in the colony had a firearm, or if they did no one wanted to kill the horse. Dr. Paul said he would do it. He got in his Travel-all, drove 500 meters.

He got out of the vehicle with his .270 rifle, nestled its custom stock against his cheek and squeezed off one of the high velocity bullets that he loaded himself.

As the astonished Hutterites watched, the high-powered slug shattered the horse’s skull and the creature was instantly put out of its misery.

Dr. Paul liked to drive from Didsbury to Calgary or Banff to spend a weekend with a friend of his who was a dentist.

The two worked together in Didsbury. They were good friends and enjoyed hunting and between the two of them they consumed a great deal of good Scotch whiskey.

Often Dr. Paul would “pour” a general anesthetic for the dentist when he was doing difficult extractions. One particular morning, the dentist was working on a patient that Dr. Paul had put under.

The anesthetic was chloroform and half way through the procedure the dentist realized his young patient had died.

“Now what are we going to do?” asked the dentist. Something like that had never happened to him before.

Without hesitation, Dr. Paul said, “this happened a couple of times in the war. There’s only one way out of it. We have to get a massive dose of chloroform into the kid’s lungs.”

They did.

And, as Dr. Paul predicted, the kid came out of it just fine. Procedures like that aren’t learned in medical school. You have to go to war to learn those techniques.

Although Dr. Paul was fearless in battle he was terrified of having anyone work on his teeth. When the dentist realized Dr. Paul needed a tooth filled, the dentist would get the doctor rip roaring drunk.

Dr. Paul was probably one the first medical doctors in the world to perform open heart surgery.

He did it for a soldier who had been shot through the heart. He repaired the heart while it was pumping and kept the chest cavity sewn open until the heart repaired itself.

“The first time we used penicillin on a patient—my God, it was a miracle. One day the poor man was dying, the next day he was walking.”

The doctor and the dentist drove back and forth between Calgary and Didsbury often and talked about the war and what it meant and how many good friends they had lost.

“The Germans came close to beating us. The had tanks with .88 millimeter guns. They could lobe a shell over a hill and take out our boys who were hiding on the other side of a ridge. There was a Canadian tank gunner who got blown out of his tank four times. Never got hurt. He went crazy. Can’t say as I blame him.”

One night, the doctor and the dentist were returning on a July 1st evening and encountered a farmer with a flat tire.

His lights were off and they almost hit him. Dr. Paul got out of his car and explained to the farmer that it was dangerous to park on the road without adequate flares.

“I don’t have flares,” said the farmer.

“Not to worry,” said Dr. Paul. “We’ll lend you some.” What he neglected to explain to the farmer was that the flares were for the 1st of July.

Dr. Paul and the dentist (who happened to be my father) set the flares a few hundred feet behind the truck, lit them and drove away.

“You could see the fireworks for about ten miles,” said Dad.

Dr. Paul recently gave his guns to his two sons—Rob, a farmer; the other, Douglas, a banker. The two boys and his daughter, Heather, have given him eight grandchildren.

He makes a point of remembering all of their birthdays and spending time with them.

Although he claims to have no favorites, he does seem partial to a grandson named Paul. When Paul was four, he complained that his older sisters were teasing him mercilessly.

He doctor checked out the statement and found it was true then took little Paul aside and showed him how to ball his hand into a fist. “Now next time one of your older sisters make life unbearable for you, hit her in the nose with that.”

Apparently it worked because Paul was never bothered by his sisters again.

The story illustrates Dr. Paul’s willingness to fight for what he thinks is right and teach his progeny to do the same.

“When we put Alberta Health Care together,” he said, “some of the doctors thought we were trying to cut their fees. We gave them adequate fees and what a lot of people never realized was that in those days only half of the fees a doctor billed were collected.

With the stroke of pen, Manning doubled most doctors’ yearly income. I think a GP who pulls in three or four hundred thousand a year is adequately compensated.”

If he could start over again, would he?

“No,” he says. “I had my day. It was a great life. There’s no way I could practice what has become of medicine.” He is not sad, nor is he resigned.

“I made some mistakes, lots of them,” he said. “When I first started my practice a young mother came into my office and I had to tell her that she had several terrible cancers. She asked me how long she would live.

“I said a few months at best. Nothing could be done. She looked at me and said, ‘Doctor, I have three children who have not started school yet. I will be around to see each of them graduate from university.’ She wrote me a note when the last one graduated. Never underestimate the power of the human spirit. Or a mother’s love.”

He chuckles and allows that he’s not certain if any of her kids wanted to go to college. But by God, their mother saw to it that they did.

“I had a lot of patients who had sicknesses that I couldn’t figure out. I often had George Law (a druggist in Didsbury) compound huge purple pills that were nothing but sugar. You would be surprised how many of my patients made total recoveries because they had something to believe in. A Goddam purple pill big enough to choke a horse. It’s a wonder they didn’t strangle trying to get those pills down. Never scoff at believing in something.”

Each day he gets up, feeds his dog, watches a little television and stops in to see a neighbor who is a Mormon. She is 94.

Dr. Paul kids her mercilessly about her religion. He does not hold much with organized religion and postulates that he and his wife will return as mallard ducks.

Dr. Paul swears he does not belittle Mormon beliefs. “I’m just having a bit of fun by pointing out the facts. In the long run facts will damage most religions beyond repair.

The two bicker about other things. She believes that after she dies, she will see all of her dogs. Over the years she has had as many pets as Dr. Paul.

“So you think then?” he asks, “that dogs have souls?”

She answers yes.

“Have you ever seen a dog’s soul?”

She tells him to talk about something else and he sips his coffee and puffs on his pipe or cigarette then, after an hour or so, he says he must return to his home to feed Ben.

By the way, the woman is my mother.

After he assembled Alberta Health Care, Dr. Paul went on to work for the Alberta Government as Chief Medical Officer in the Rehabilitation Clinic at The Workman’s Compensation Board.

He has little time for chiropractors and even less time for new age medicine, although he would be the first to admit that the best religion that he has seen on earth is that of our natives.

“They have reverence and appreciation for nature. That’s a good thing.”

He can identify most wild trees, bushes and flowers.

“You know what will kill you in the bush? Your watch. You get lost and then you remember you have to be home for dinner at six and you panic and you really get lost and you trip and you break a leg and a bear eats you. If you’re ever lost, take off your watch and throw it away. Forget about time. Focus on staying alive. Build a fire and start thinking.”

He understands the ebb and flow of the seasons as only an Albertan can. And he believes that the weather can be predicted by observing how beavers build their lodges.

He is fascinated by mushrooms and with his microscopes (he has two), he is working on a single test that will identify poisonous or edible ones.

“Did you know there’s a kind of mushroom in Northern Alberta that will kill most people if they eat it, except if you’re a Russian, then you have a genetic immunity to it. Nature is fascinating.”

Lately he finds himself thinking more and more about what will happen on the other side of this life.

“I had a stroke several years ago and I was out of it for a week and I kept having this dream. In the dream I was back in the war and every man I knew who had died was waiting to get on the conveyor belt. I knew each man and called him by name.

“In my dream there was a terrible commotion and I realized that someone was refusing to get on the belt. I saw that the man was me. I knew then that if I woke up I would be alive. I woke up.”

Death doesn’t haunt him. He finds it as fascinating as say, mushrooms. He knows that shortly he may have a few answers to questions he has wondered about all of his life.

Until that time Dr. Paul still enjoys planting roses, walking his dog and chuckling over his take of the inconsistencies of the universe. Every week he vows he will stop smoking.

He is by nature a frugal man in many ways. He does not like paying exorbitant prices for tobacco. And he is annoyed that although he has been able to master almost everything in life, tobacco has outsmarted him.

“I might live to be a hundred,” he says. “But then again, there’s a chance I won’t.”

He taps a cigarette from a pack and touches a match to the tobacco and inhales deeply.

Like to read another story about Didsbury?